Reflections on Artist Costantino Nivola

by updates@lform.com

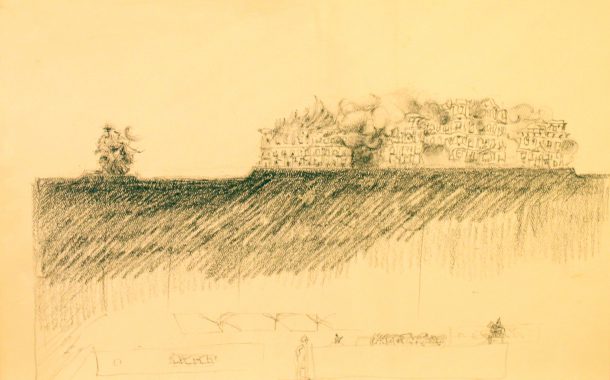

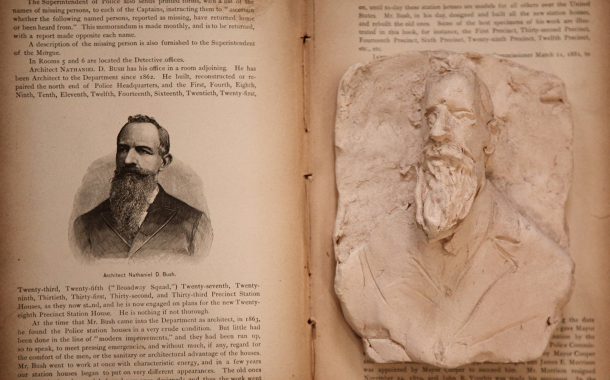

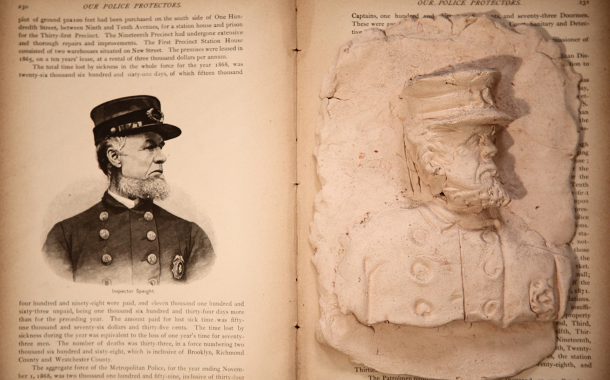

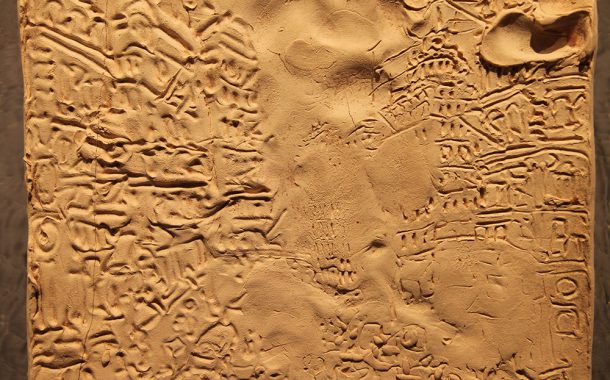

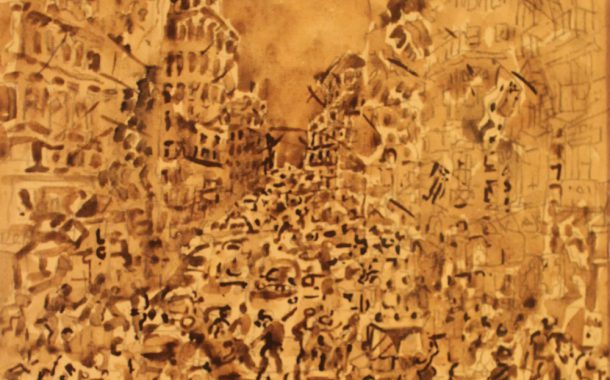

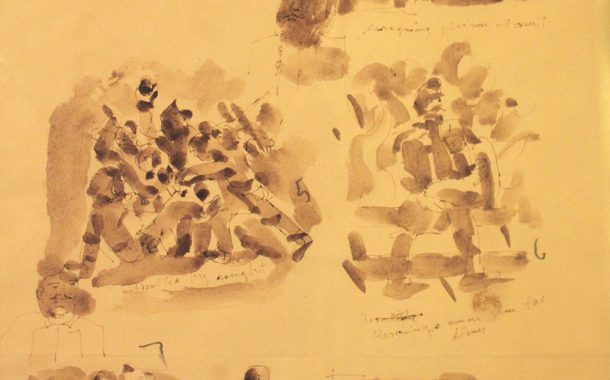

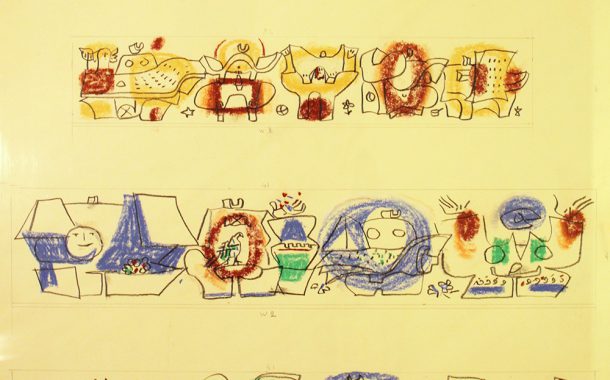

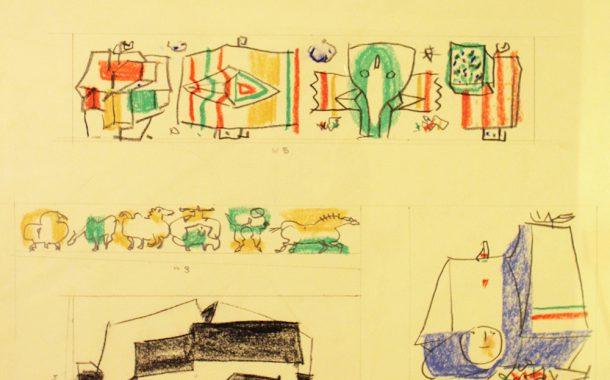

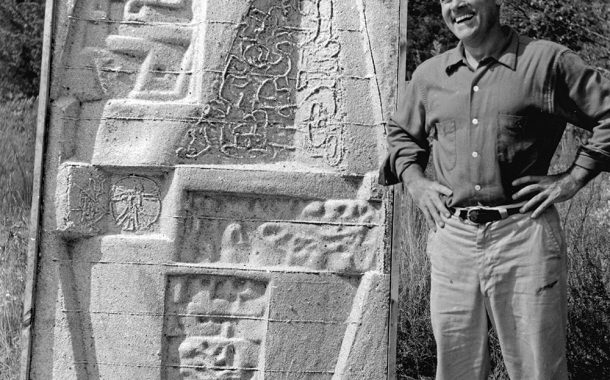

Reflections on the Artist: Costantino Nivola. A collection of images from Carl Stein's recent presentation at the Italian Embassy in Washington DC It’s not possible to describe Costantino Nivola – Tino – in a few paragraphs or a few pages. His art as well as the sum total of his life have far too much range and depth. Rather than making a futile attempt at comprehensive inclusion, I will try to add texture to his accumulative portrait by sharing some personal recollections drawn from more than thirty-five years of knowing Tino as a mentor, a colleague and a friend. I think I was nine or ten when my parents first brought me to visit the Nivola family in The Springs on Long Island. While I’m not sure of the exact year, I do have evidence that by 1956, when Tino was working on studies for a large multi-panel sand-cast relief for the Grady High School in Brooklyn – one of his early collaborations with my father Richard Stein, I, as a thirteen-year-old, was already hanging around with my most-prized possession, an inexpensive Japanese knockoff of a Rolleicord. Interestingly, not only is this image of Tino, standing by the maquette of the Grady relief one of the few early photographs of mine that has survived, the maquette in the photograph was in my possession until a few years ago when I gave it to a young colleague who is fortunate enough to have a loft large enough to display it properly. It is still there, having been passed from Tino to my father to me and then to him. An unintended although quite relevant reading of the photograph might be that of a dual portrait, a diptych – Tino and friend, and might speak of the equivalency between the artist and the art. The image of Tino conveys an overarching sense is of immediacy and connection, intense and complex. The art is somewhat more aloof, the figure being a representation of idealized humankind, an iconic graphic. Yet within the structure of the grand figure there are pictograms of more mundane events, suggesting that integral to the conceptualized essence of the primary figure are daily human activities; and that these activities are not only essential to basic existence but are the undertones and overtones that flesh out a fully engaged life. Looking back to the artist, underlying, or perhaps emerging from the immediately apparent warmth and passion is transcendental dignity and intellect. Micro and macro, macro and micro. Any discussion of twentieth century art must clearly distinguish between narrative subject on the one hand, and conceptual subject and formal structure on the other. The narrative for Tino’s work almost always involved the human experience, and throughout his career, this narrative oscillated between the micro and macro perspectives. In many works including the figures for the Piazza Satta and the Combined Police/Fire Facility in New York City, subtle representations of daily activity imply a grandeur far beyond that of either the scale or literal reading of the narrative. In others, such as Grady relief, the primary formal theme speaks of elemental human dignity, yet with footnotes addressing events that give human life warmth and color. The choice of one point of view or the other was never one of absolutes nor did it follow any particular time line. Consider, for example, the similarities in perspective between the Masculine Figures from the mid-1950’s and the Feminine Figures from the early 1980’s, or between the Piazza Satta figures from 1966 and the Combined Police/Fire Facility figures from 1984. Between 1954 and 1971, Tino and my father collaborated on a number of projects –playgrounds including Stephen Wise Houses in Manhattan and PS 55 in Staten Island, a building which also incorporated four large concrete reliefs integrated into the facades; other schools such as IS 183 in the Bronx; and public spaces, in particular the Piazza Sabastiano Satta in Sardinia. During this period, I was going to school, eventually getting my architectural degree from The Cooper Union, and then working for Marcel Breuer. In 1971, I joined my father’s firm. One of my earliest assignments was working with Tino on the architectural components of the memorial to Antonio Gramsci (unbuilt). The project consisted of three figures, approximately life-size, populating and open-topped room whose walls and floors were to be blocks of local stone. The front wall incorporating the single opening into the space and the back wall sloped away from the front. This created an inherently unstable condition at the top of the entry. The solution was to add walls on either side of the entry, parallel to the side walls creating a short, narrow passageway whose ceiling – the underside of the front wall – sloped sharply upward. I remember Tino’s delight at the tightly controlled views and the spatial fluctuations that resulted. His interest was not only in the objects, the sculptures themselves, but in the experience of encountering them and the contextual message inherent in the enclosure for the Gramsci figures. The lesson of the experiential power of entry, for architecture as well as for art, was not lost on me. Following this were the ongoing activities involving Tino, my father and myself dealing with the completion of various commissions including the large sculpted concrete pieces for IS 183. There were also many lunches when Tino came to the office to discuss some aspect or other of the works in progress, but for ten years, there were no new commissioned collaborations. In 1981, I got a phone call from Tino asking whether, for a few months, during the mid-week, he could use the guestroom in the house in Greenwich Village where my wife, daughter and I live. He was working on a series of paintings of New York and wanted to spend time sketching the city. We, of course, said yes and for a number of months, Tino would arrive on Monday or Tuesday and stay until Thursday or Friday. Some evenings he would go out for dinner but more often, we all ate together. On a few special occasions Tino cooked, preparing his own variations on Sardinian cuisine. Even more memorable than the food was the conversation. One evening, Tino pulled out some drawings of lower Fifth Avenue, looking south toward the Flatiron Building. The view included a number of the late nineteenth century loft buildings that lined the street. The drawings stressed the horizontal lines of the column capitals about fifteen feet above street level, implying a plane parallel to the street but overhead. The pedestrian zone became a strongly felt volume bounded by the buildings, the sidewalk and the new surface suggested by the capitals. Tino remarked that Le Corbusier had frequently said that most new architecture failed to use the weight of the building to define the ground. By this time, I had become a partner with my father. In early 1982, we received a commission to design a new Combined Police/Fire Facility on East 67th Street in Manhattan for which I was the partner-in-charge. The project was to incorporate the facades of two freestanding Victorian buildings which would be restored as part of the work, and to connect them with new building fabric. The facility, which would provide an entirely new state-of-the-art headquarters for a police precinct, fire company and the Manhattan arson squad, included an allowance for artwork. I proposed to the City that Tino be commissioned for this work, suggesting that something loosely related to his recent New York City drawings serve as the basis. Happily, both the client and Tino accepted, starting what was for me one of the most exciting collaborations of my career. Tino’s plan was to create a set of narrative sculptures speaking to the history and work of the Police and Fire Departments. In the course of my investigations for the restoration of the two facades, I had come across a book called Our Police Protectors published in 1885, contemporaneous with the 1885-6 construction date of the two buildings. The book contained a none-too-accurate drawing of the then under construction precinct station but it also chronicled Police Department work and included a number of etchings showing both nineteenth century police activity and portraits of many of the NYPD officers. These, along with photographs from the museums of the Police and Fire Departments became the narrative subjects for what turned out to be Tino’s last public commission in the United States. Interestingly, although the pieces that were created for the Combined Facility were envisioned to be “architectural sculpture,” they are more closely related to the figures for the Piazza Satta as well as the “Beach” and “Bed” terra cotta series from the mid-70’s, than to the earlier angular concrete architectural works. Similarly, the large relief of the city is “drawn” with reference to the New York City drawings from 1981-82 as well as the Chicago drawings of 1968, the Citta gremite drawings of 1947 and the Veduta di New York paintings dated 1943-65. During the first few months of this project, Tino returned to his schedule of spending weekdays in New York City. He and I visited various archives looking for subject material for the works. When a likely image appeared, we would discuss how a sculpture based loosely on the particular image might be incorporated into the architecture. An underlying criterion was to create and present sculpture that conveyed the importance of civic and public commitment while, at the same time, demonstrating that civic action could be incorporated seamlessly into daily life. Once the raw material was selected, Tino returned to working in his studio in The Springs, creating first a series of sketches and very preliminary maquettes followed by more detailed maquettes. These were presented to and enthusiastically accepted by the clients. Tino then made the final sculptures in terra cotta and sent them to The Modern Art Foundry in Astoria. Because of the size of the relief panels and the complexity of some of the freestanding sculptures, a number of the works were cast in several pieces, to be welded and finished after removal from the molds. Tino oversaw that process as well as the final finishing and application of patina. On several occasions, I accompanied him to the foundry. In what I remember as being late autumn in 1987 when Tino and I were returning from a visit to the foundry, we were driving down Fifth Avenue giving us a similar perspective to what had been the starting point for the large relief to be installed in the lobby of the police station. Tino reflected somewhat sadly that with all of the pressures of contemporary life, people – or artists – weren’t taking the time to simply gather quietly, enjoying and discussing their work – or perhaps it was that the time just wasn’t there to take. This observation has remained with me for nearly twenty-five years and, when I restructured my office about five years ago, a key organizing principle for my colleagues and me was that it be structured to encourage these discussions, not only to take the additional pleasure from the process but equally to encourage the synergistic growth and development that only comes when working in a strongly-felt creative and intellectual community. That trip to the foundry and the return drive were to be the last project meeting I had with Tino who died the following May. Due to construction delays and contractor failures, the building did not open until 1991. Working closely with Ruth Nivola, we oversaw the installation of the sculpture. The sculpture at the Combined Facilities along with all the artwork – the bronze, stone and concrete, the large maquette in the left of the 1956 photograph – carry Tino’s creative DNA; however for those of us who had the good fortune to know and work with Tino, there is also the presence of the man – the intense, smiling figure in the right of the photograph, which remains fundamentally undimmed. Notes: 1. Much of this material has been extracted and adapted from a project with Giuliana Altea and Antonella Camarda documenting and analyzing the architectural collaborations and unbuilt projects of Costantino Nivola 2. For photographs of sculptures referenced here but not pictured, see Costantino Nivola in Springs, Micaela Martegani, 2003. 3. For copies of drawings and paintings referenced here but not pictured, see Seguo la traccia nera e sottile – I disegni di Costantino Nivola, Giuliana Altea, 2011